Affirmative Consent: Shifting the Culture

By Gina Lepore MEd | July 20, 2015

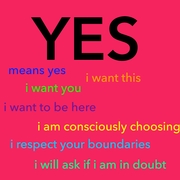

Yes means Yes. Yes, I want you. Yes, I want this. Yes, I want to be here. Yes, I am consciously choosing this now. Yes, I respect your boundaries. Yes, I will ask if I am in doubt. More, please!

Last September, California became the first state to pass legislation that sets a new standard for sexual consent on college campuses receiving state funding for financial aid. This legislative act followed policy changes on consent at several universities across the country. Systems have continued to adopt affirmative consent standards, including the State University of New York (SUNY) system.

Sexual Assault on Campus

In recent years, reported sexual assault and rape cases on college campuses have been on the rise. The media has reported on cases at schools such as Duke, Dartmouth, Florida State University, Johns Hopkins, Stanford, Tulane, UCLA, and Yale, among others. Google the name of just about any college plus the word “rape” and the results may be surprising. Meanwhile, many universities appear to be undercounting campus sexual assaults.

Some survivors of sexual assault have criticized the institutions where they were enrolled. Others have filed formal complaints or lawsuits. These critiques cite violations of Title IX requirements, including the presence of policies and practices that foster a hostile, unwelcoming, or discriminatory environment for survivors.

In 2014, the Obama administration formed a task force to address these widespread criticisms. The U.S. Department of Education (DOE) initiated an investigation of colleges and universities throughout the country. One outcome of the investigation was a report that listed schools under investigation for faulty sexual assault policies and practices.

As a result, a number of campuses examined and redefined their policies on sexual consent between students. It is important to note that many schools had affirmative consent policies in place well before these current controversies. Antioch College, a liberal arts school in Ohio, was the first college to include such language in its policies, back in 1991.

Shifting the Culture

The new policies can be summarized most simply as a shift in responsibility for obtaining consent in sexual encounters. Under many former (and currently existing) policies and laws, the victim (survivor) of a sexual assault had to prove that he or she tried to stop an encounter, either verbally or physically. This was the only way to legally prove that the sexual contact was unwanted.

These policies allowed for successful prosecution of some perpetrators, but only to a limited degree. There was no redress in the numerous situations where psychological or verbal coercion or intimidation affected someone’s ability to utter a clear “no.” The policies did not address the use of drugs or alcohol in combination with sexual activity, which makes it difficult for either party to consciously give or obtain consent.

The intention behind these new policies is to place responsibility on all parties involved to both obtain and offer a clear and conscious “yes” prior to and during sexual activity. The hope is that this shift will greatly reduce the gray area that has previously existed under “no means no” policies.

Many young adults feel this legislation is a step in the right direction and has the potential to create change. They also recognize that it’s necessary for institutions to disseminate adequate information and education about the policy. Take a look at the video accompanying this post to hear some young people eloquently express these views.

It seems that Americans of all ages, all across the country, feel similarly. This is not a universal sentiment, however. Those opposed to affirmative consent policies have been outspoken on the issue, and include college students and other young adults.

The Debate

Some people feel intimidated by affirmative consent policies for a range of reasons. They may never have been taught how to talk about desires and boundaries. This leaves people feeling unequipped to navigate the types of conversations affirmative consent requires.

For others, this approach to sex runs cross-grain to everything they have been taught about sexual interactions. They’re looking for spontaneity and “magical” passions—powerful feelings of attraction that emerge suddenly, are felt equally and similarly by all parties, and require nothing so plain as clear communication.

Some critics of affirmative consent policies call them unrealistic and unenforceable, backed by complaints that “that’s just not how sex happens.”

This sentiment begs the question of exactly how sex does happen for some people. Many of us have been raised with social norms and sexual scripts that actually support non-consensual sex. I would suggest we first examine these scripts and understand how they affect our sexual interactions before we criticize attempts to change them through policy shifts.

Slut-shaming, victim blaming, the eroticization of rape and the ways men are taught to perform their masculinity all contribute to these scripts and norms. Jane Phillips, in her documentary film Flirting with Danger, describes the phenomenon known as Rape Culture as “a culture in which dominant cultural ideologies, media images, social practices, and societal institutions support and condone sexual abuse by normalizing, trivializing and eroticizing male violence against women and blaming victims for their own abuse.”

On some level, these ideologies and practices have not been adequately addressed in sexual assault prevention messaging. Thus, although considerable progress has been made in recent years in supporting survivors of assault, the same is not true when it comes to changing attitudes and beliefs about the abusive approach to sex that causes assault in the first place.

It’s time to debunk the myth that sexual violence is a women’s issue. It is actually a men’s issue. People of all genders, including trans-identified individuals and those who are gender fluid, have been violated sexually. Sometimes females are sexual aggressors. Far more often, aggressors are male.

I'm not suggesting that "men," per se, are the issue. Rather, it is the harmful ways men are encouraged to approach sex. Troublesome norms may be promoted by family or peers. They are patently apparent in popular media and pornography. At times, the entire culture seems to acquiesce in or support negative sexual norms for men. We would all benefit from wider promotion of healthier approaches to male sexuality.

A number of organizations and campaigns are working to address this truth (We End Violence, Men Can Stop Rape, Mentors in Violence Prevention, It’s On Us). These efforts are crucial to building the momentum we need to put affirmative consent policies in practice in a way that shifts the burden of responsibility for obtaining consent from the assailed to the assailant.

Affirmative Consent Policies Offer an Opportunity

Affirmative consent laws provide sexual health educators with a valuable opportunity to help young adults develop the communication skills necessary to have safe, fun, respectful intimacy with their partners. I speak regularly at local colleges about sexual communication. The feedback I hear repeatedly from students is that there is an enormous need for young adults to have some clear strategies for developing these skills. They also need a safe space in which to practice them.

While some youth received information in high school about pregnancy, HIV and STI prevention, most have not been educated about how to talk with partners about both their boundaries and their desires. It isn’t enough to teach high school students how to say No. We also need to teach them about healthy, safe, respectful ways to say Yes.

This education can start right now. There are some great comics and short videos already available for educators to use in the classroom to start conversations with their students.

Change is hard, but necessary. For too long, existing campus sexual assault policies have been failing victims. Affirmative consent policies will not completely eradicate the challenges of preventing and prosecuting cases of sexual assault. They will not immediately change attitudes and beliefs. But they will support a cultural shift around how sex happens. It is time for educational institutions to formally support an approach to sex that values communication, respect, agency and consent above all else.

Gina Lepore, MEd, is a human sexuality educator and a Research Associate at ETR.