How to Go Beyond Equality to Achieve Equity

By Julie Potyraj, MPH | August 14, 2018

External Relations Manager for Content Marketing, 2U Inc

I have seen the power of health equity in my life as a woman living in the United States and as a public health professional working abroad in rural Zambia. Equity meets people where they are, and acknowledges that different problems require different solutions, depending on the context.

A significant part of our life experience is shaped by our personal circumstances—who we are, where we live and the opportunities we are given. Consider:

- If you’re female, doctors will be more likely to ignore your pain and misdiagnose your heart attack or stroke compared with male patients.

- If you’re a black student with ADHD, you are more likely to have teachers dismiss your symptoms as misbehavior compared with white students.

- If you’re a girl interested in science, you are more likely than a boy to be deterred from studying STEM subjects.

- If you’re growing up in a low-socioeconomic community, chances are you’ll have less access than those in wealthier communities to resources that support better health and quality of life—excellent schools, safe neighborhoods or grocery stores with fresh produce.

These realities go by different labels. Health disparities. Economic inequality. Achievement gap. But they all arise from the same sources: systemic racism, gender bias, cultural ignorance and other entrenched hurdles. How do we right these imbalances? The answer is equity. Specifically, we need policies and interventions that reduce inequality by tackling their root causes.

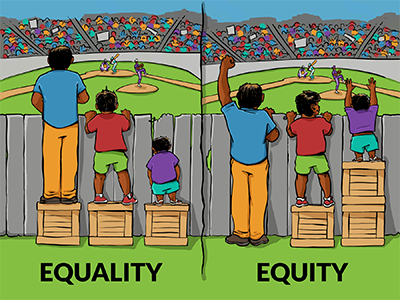

One step in this effort is to build clear understanding about the distinctions between equality and equity.

Equality vs. Equity in Zambia

Gender equality, for example, is a global mission that will only be accomplished through the implementation of programs focusing on equity. Providing women and men equal opportunities would assume that women and men started on an equal playing field and had equal abilities to actually access those opportunities.

I spent more than three years working with education and women’s empowerment programs in Zambia, a sub-Saharan African country with approximately 17 million people. Like women in many other countries in the region, women in Zambia face disproportionate negative effects from social determinants of health, compared with their male counterparts. Women must cope with early marriages, sexual abuse, early pregnancy and restricted access to educational, health and economic resources.

As a result of these and other factors, Zambia has had a high maternal mortality rate.

Putting the Health Equity Lens to Work

When I worked in Zambia, programs for women considered how to best ensure that women got the care they needed. We had to consider the factors that made women vulnerable to these problems. An equal approach might make similar health services available to men and women. An equitable approach would provide accessible services that addressed women’s specific needs and concerns.

In the rural area of Eastern Zambia where I worked, there was a clinic in town that provided services for men and women. However, the district health offices had difficulty encouraging women to come in for prenatal and postnatal services.

Women wanted these services. Yet even though they were available at the clinic, women weren’t able to access them. Women in the more rural areas often lacked transportation, or the money needed for transportation, to reach the town clinic. The clinic was open during the day, when most women were performing household duties or working in the fields.

Additionally, the clinic was in a very public place. Due to cultural stigmas, women did not always feel comfortable seeking sexual health services where they might run into distant neighbors or extended family members. I often saw women opt out of medical care during pregnancy because they weren’t able to access it, even though they knew it was there.

Some local NGOs understood these obstacles. They provided mobile clinics to visit women in remote villages. They provided vaccinations, OBGYN services, STI testing and basic medical treatment. Women were able to visit these mobile clinics because they caused a less noticeable interruption to their daily routine.

By taking into consideration the individual needs of these women and the challenges they faced, health NGOs were able to provide treatment to more women who would have otherwise gone without medical care.

Ways We Can Promote Equity

An illustration created by Angus Maguire for the Interaction Institute for Social Change highlights the differences between equality and equity beyond public health. Understanding the distinction is critical to eradicating the injustices that curtail a person’s potential. An article by MPH@GW, the online MPH program at the George Washington University provides additional examples of equity in action

The road to equity starts with a focus on both the destination and the roadblocks. In public health programming, this can be a useful way to address health disparities in a given community. We must identify the disparity and desired outcome or need, evaluate specific barriers, then provide solutions that overcome said barriers.

The road to equity starts with a focus on both the destination and the roadblocks. In public health programming, this can be a useful way to address health disparities in a given community. We must identify the disparity and desired outcome or need, evaluate specific barriers, then provide solutions that overcome said barriers.

One useful resource is the Talking About Race Toolkit created by the Center for Social Inclusion. It focuses on advancing racial equity, but its strategies can be applied to combat other types of inequities, such as those faced by the LGBTQ community, people with disabilities or organizations seeking to create more gender-equitable workplace environments.

This lens of equity can be applied not only to public health initiatives, but while evaluating workplace decisions and throughout everyday life. Making this adjustment to thought and behavior can transform relationships, organizations and communities.

Julie Potyraj, MPH, is the External Relations Manager for Content Marketing at 2U Inc. She received her Master of Public Health degree from the MPH@GW program at the Milken Institute School of Public Health at the George Washington University. Prior to her work with higher education, she spent several years working with community development, women's health and girls education in rural Zambia.